The woman I knew throughout my childhood as Gramma Harriet was my mother’s stepmother. Mom’s parents had divorced when she was a teenager, and her dad, my Poppy, had married Harriet a month before I came into the world. By the time I was a couple years old, I could already feel the frostiness between my Mom and Gramma Harriet. While the two did become closer over time, for 20 years or more, just hearing my mother say the name Harriet meant that what would follow was probably going to be tinged with disgust, exasperation, or some other form of acid.

I’m sure that Harriet’s greatest sin in my mother’s eyes was that she was not and never would be her mother. Like many children of unhappy marriages, my mother spent most of her life wishing that her parents could just get back together so that everything would always be as wonderful as it had been on what I came to understand was only a very few occasions. My mother adored her father and thought he was the best, smartest and handsomest man in the world. How could anyone, much less this latecomer Harriet, be good enough for him? That’s what I gathered without her ever saying those words.

Harriet was a presence: attractive if not pretty, stately, friendly and humorous, if a little brittle. She was elegant, always well-dressed, perfectly groomed and sure of herself. She was very kind to her grandchildren, and did a number of thoughtful things for us, but in the way of a career woman. She was not an aproned granny who cooked and cleaned or sewed. She went to work every day at Saks Fifth Avenue, in a department that my mother asked for, when she phoned her at work, as “Ladies Better Suits and Coats, please.”

Harriet seemed to know the ways of the rich, and in a few visits to her at work, I saw her not as a retail saleswoman, but as a respected member of a hushed, carpeted, mysterious domain where one used the strange vocabulary of fashion and revered the quality of fine garments and fabrics.

For my entire life, there has been a shade of coppery bronze silk that will forever mean Harriet to me, because it was a favorite of hers. I was fascinated by her clothes, her perfume, and her leather luggage: none of them existed elsewhere in my life. What went along with it all was her cocktails and cigarettes. Many years after Harriet died, someone gave my husband a gift of a certain whisky that, when I smelled it, brought back in a rush Harriet’s omnipresent icy drinks garnished with lemons. Both Harriet and my Poppy died too early, in their 70s, a couple decades after we had all moved to different states and rarely saw one another. Harriet suffered terribly with throat cancer.

Only another couple decades later did I begin to really learn anything about Harriet’s life. I work on genealogy with a passion. After years of researching my ancestors, I realized I had not looked at Harriet’s life at all. She was not my blood relative; she had no children that I knew of; it never occurred to me to look into her facts. When I finally turned to the story of Harriet Jones Hamilton, I was regretful that I had never known the real woman.

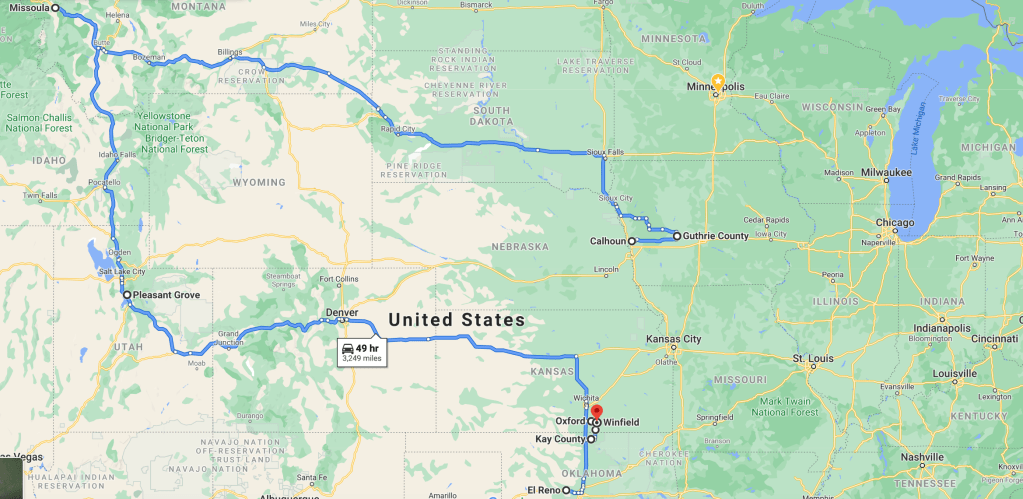

The golden Harriet Hamilton started life humbly in 1908 as Harriet B. (known as “Bee”) Jones in Oxford, Kansas, the daughter of a repairman in the gasoline industry. By the time she was 2 years old, her family had moved 150 miles south to El Reno City, Oklahoma. Her parents had been married 16 years by that time, and her four older siblings had been born, respectively, in Calhoun County, Iowa, Guthrie County, Iowa, Missoula Montana, and Pleasant Grove, Utah. I don’t know why. When they first married, her parents lived with her father’s parents, farming in Oklahoma.

In 1916, when Harriet was eight years old, her father died, 150 miles west of El Reno City, in Muskogee, Oklahoma. Her mother remarried three years later, about 120 miles northwest in Kay County, Oklahoma. In 1920, the family of nine now named Barr lived in Arkansas City, Kansas. They had returned in a circle to the general vicinity of Harriet’s birth on the Kansas-Oklahoma border. That may explain why Harriet seems, if her high school yearbook is to be believed, to have had a relatively happy time as a glee club member and evident cutie-pie at Winfield High School in Winfield, Kansas.

She didn’t graduate, though (according to a later census); after moving away from home to live with her older, married sister Minnie at 17, Harriett married, in 1928 when she was 20, the handsome, tall and slender Harold Dee Grove. Harold worked at the local newspaper in 1930 as a stereotype (there’s a job!). Bee, as she was known, and Harold Dee were still married in April 1940, living in Winfield. She worked as a seamstress at a tailoring shop (clothes from the start!) and he as a cook. But the two divorced later that year, and in October Harold was living with his mother, as he did for the rest of his life. They had no children.

The many changes during WWII brought Harriet to Detroit. In 1945 in that boom town, she married Clifford LeRoy Johnston. There is no record of their lives in the seven years of their marriage, but soon after their divorce in June 1952, she married my Poppy, Bob Hamilton, in Detroit, and they were a good and loyal couple until her death in their new home of Rockford, Illinois in 1984.

What a life. Behind the picture of smooth big-city elegance, a hardscrabble life on the dusty plains with shallow roots. Throughout her years, she worked and married and tended to the small garden of her life with several husbands. Who was she, I’d still like to know. What did she dream about and love, and what gave her joy? Almost no one now alive knows her. This is my attempt to leave some record or tribute that will honor and provide a picture of the life of Harriet Bee Jones Barr Grove Johnston Hamilton.

A postscript: In 2025 I read The Worst Hard Time, winner of the National Book Award in 2006. This excellent history by Tim Egan brings alive the experience of those who lived in Harriet’s corner of the world in Kansas-Oklahoma in the years from the turn of the century through the 1930s. I recommend it highly to anyone wanting to understand their family in the dust bowl era–or to any American who wants to know more about the causes and impact of those dramatic changes on the Great Plains.